“You have been involuntarily recalled for active duty. You are to report to the unit tomorrow morning at 7:30 a.m.”

My mother stops reading, collecting herself, as if putting herself back in some box.

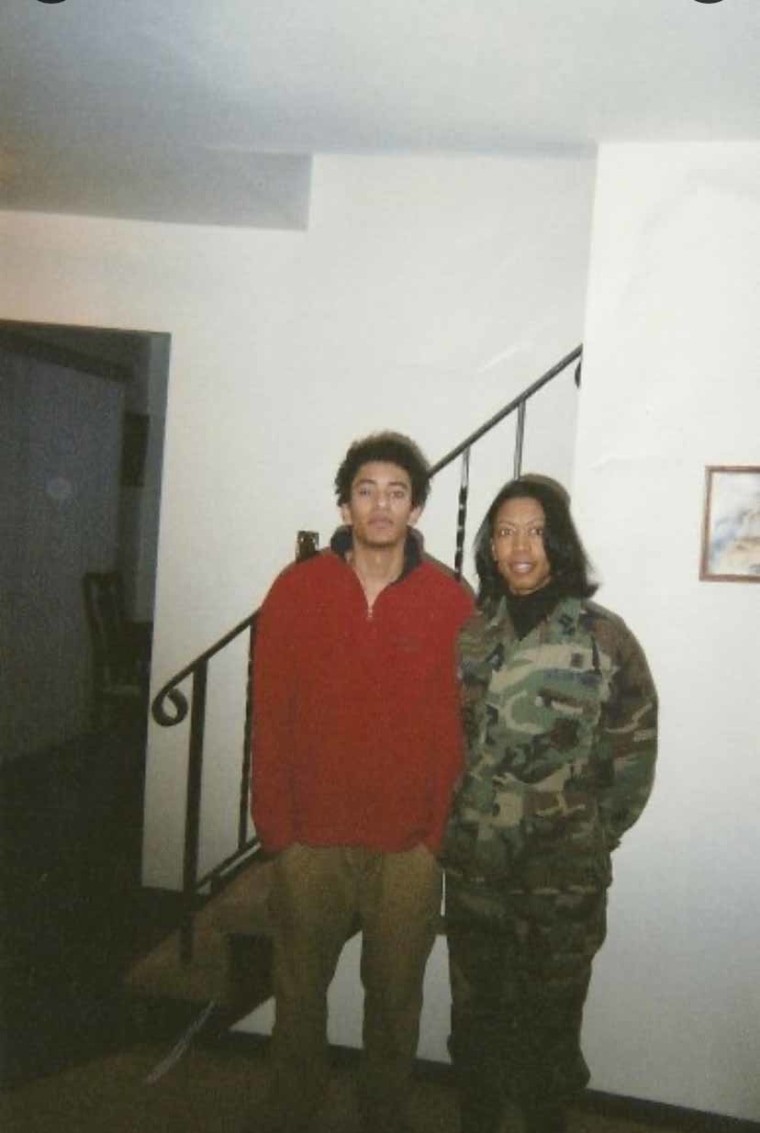

Later that day, I find her rummaging through her closet. She should be at work. I always get home from school before everyone else: Mom, my little brother, my stepfather. I am a teenager, 15, and have plans to do some teenager thing — watch something I’m not supposed to or have a girl over and I am more worried with that, her being home unexpectedly, than why my mother seems so upset and is gathering her clothes. The skin under her eyes is puffy.

“I’m packing my bags and leaving tomorrow. You won’t come to the base with me. We’ll say goodbye — ” and she stops, hitting a wall, knowing that saying it is affirming it, “say goodbye here, and I’ll go to the base. I’m not sure where they’re sending us yet, but it’ll be OK. Everything will be OK.”

“Mom?”

“Davon, I have to go to war.” Her voice stops like a jam between gears.

We’ve been waiting for this day, in some ways, since America went to war after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks. It’s 2003, and my mother has to go to war.

She stops, and it seems she’s choking on her words. Her bed is covered in her clothes, and a thin layer of sweat greases her face. Maybe she hasn’t said it out loud yet, but she speaks as if confronting a fear that is now very real for the first time.

"I have to go to war.”

In such a short sentence, she covers enormous ground — leaving her family, deployment to another country, the dangers of war. But I signed up for this, maybe she thinks; she did, and has been in the military for over twenty years.

She joined the military because, as she told me many times before, 'I was a poor Black girl who didn’t have many options.'

My mother was Active Duty in the U.S. Army from 1980-1983, the U.S. Army National Guard from 1984-1987, the U.S. Army Reserves from 1987-1993, and she joined the U.S. Air Force in 1994, where she has been an officer since. She’s made a successful career in the military and is a captain. She works as a civilian nurse when not on McGuire Air Force base.

She joined the military because, as she told me many times before, I was a poor Black girl who didn’t have many options. She’d tell me about her brother, her sister, her uncles, her grandfather, her people, Black people, through World War II, the Vietnam War, and the eventually, the War in Afghanistan. She’d tell me how so many Black Americans enlisted in the military for an opportunity that this country, yet again, demanded of Black bodies, as if to say We will give you your rights if you will sacrifice for us, will fight for us, will die for us.

After serving in the Army Reserves until 1992, my mother applied to nursing school and finished her degree in 1993. Becoming a nurse, both civilian and military, is what helped my family relocate from an apartment to a single-family home in suburbs. Education, as she always said, was most important.

For all my life, my mother has been in the military, and I always remember her dressed in two ways: fatigues or scrubs. This is how I see her, returning from the base in her uniform, or from a twelve-hour shift at a hospital.

We microwave Chef Boyardee. We order pizza, and not just on Fridays. We pile dirty clothes in heaps.

The average deployment length is six to twelve months, and my mother has only been gone for 15-day training stints on various military bases: Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama, Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, Yokoto Air Force Base in Tokyo, Japan.

When she is gone for those two-week trainings, my stepfather, little brother, and I barely get by. We microwave Chef Boyardee. We order pizza, and not just on Fridays. We eat Chinese takeout leftovers through the weekend. We pile dirty clothes in heaps. We leave unopened mail on the kitchen table.

But this is different; this is war, which started over two years ago, since the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

We finally say goodbye to her in the morning before school. She brings me close, fitting her face on my teenage chest, and it takes my breath away, completely, and I am breaking down, heavy sobs because I might not see her again.

My little brother is waist-high, and she kneels to his height and gives him the same embrace as if she’s cocooned him, as if she’s bringing him back inside of her, as if she can hold him there, just a little longer, just to be her little baby again. When she lets him go, he cries, but differently than me, just runny nose and snot and Mommy-don’t-leave-us, but he really doesn’t understand and thinks she’ll be back home tomorrow.

My stepfather is stone, and he waits without a word. They don’t even hug each other. They just stand there as if they’re talked-out, as if the emotions of departure, of their marriage, has already been exhausted. He’s exhausted, and so is she. He carries her military-issued duffle and is carrying something else, something that looks like a man who is realizing he’s now lost.

She seems to stand at attention, her body taut, her skin tightened, muscle memory. She’s wearing her military fatigues, detailing her rank and position. I don’t know much about this but know she’s a high-ranking officer, a Black officer, a Black high-ranking woman officer in the United States Air Force, and I’m proud to be her son.

She tries to call as much as she can, but we’re sad when she does and sad when she doesn’t.

We wait by the phone a lot. My mother is deployed to Ramstein Air Base in Germany. We’re grateful she’s not in Afghanistan, or Iraq, or Qatar, or wherever we think the war is. Germany is six hours ahead. Whenever the phone does ring, we sprint to the various phones, picking up the receivers eagerly, angrily — frustrated she’s still not home, frustrated that we’re falling apart without her, that I’m barely passing my classes, my little brother is not socializing, and my stepfather is living every day on a pencil-thin edge. Our voices jumble, a mess of what-happenings that happened since last we talked. She is working when we’re home and is off when we’re asleep. She tries to call as much as she can, but we’re sad when she does and sad when she doesn’t.

When my mother returns home from war, she is with us but not really with us.

On the day my mother comes home, it’s been almost ten months. We wait at McGuire Force Base with hundreds of families. There’s a news van too. There are countless signs, big posters: “Welcome Home,” “We love you,” “Thank you for your service,” “Heroes.”

She finally makes it through the crowd. She’s wearing her official uniform, the Hap Arnold Wings, blue jacket and slacks, a blue hat, her rank insignia.

Describing how proud we felt of her in that moment is almost impossible. We saw her, and we saw the American people celebrate, honor, and value my mother and her fellow soldiers’ sacrifices — not putting her in a box as a Black American but as a solider, not a woman but a soldier, not a Black woman but a soldier. In that moment, cheering, crying, and loving with all the other families, we yelled, “Mom,” until she found us.

When she returns home from war, in the days, weeks, and months later, my mother has changed. It’s not just that she doesn’t cook anymore, or pack our lunches, or fold our clothes, but she longs for an independence that she no longer has — the kind she had when she was away.

When my mother returns home from war, she’s accepted into a master’s program; she’s going to be a nurse anesthetist, and she’s busy with school. When my mother returns home from war, she is with us but not really with us. When my mother returns home from war, she decides she no longer wants to be the same mother that she was. She’s going to be so much more.

As a kid, I didn’t understand my mother’s change. It seemed selfish. It seemed like she was giving her life a new start, and giving our life some kind of pass-over. But now, as an adult, I understand more deeply how my mother, and so many women, had to choose between their families and their careers. I understand that these women not only sacrificed their bodies, but sacrificed their dreams.

Men, fathers, are not defined by how much they cook, how much they tend to the home and the children; men, fathers, are defined societally by their careers. As a parent now, I understand how much my mother and my stepfather sacrificed while she was deployed at war. They both gave themselves for us. Military families just do that, instinctually. They have to.