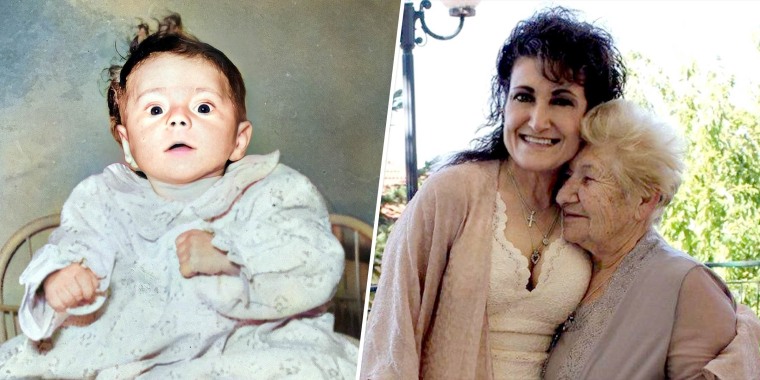

For most of my life, my name was Linda Carol Trotter, nee Forrest. I live in Franklin, Tennessee and grew up in Houston. I knew I was adopted from Greece in the 1950s, but aside from trips to Greek festivals and reading books about ancient mythology, I didn’t have a significant connection to the country I came from.

All that changed six years ago when I got an email saying my biological mother was still alive — which meant everything I knew about my past was a lie. My paperwork said I was a “foundling of unknown origins.” My parents were told my biological mother had died in childbirth. Neither was true.

I’ve heard a lot of adoptees say, “There was always part of me missing.” I honestly never felt that way until my parents both died. Growing up, I had the kind of parents every child deserves — kind, loving people. They adored me, and I adored them. Considering the adoption process had no oversight from either the Greek or U.S. governments at the time, I was extremely lucky. Greece did not pre-adoption screening; the U.S. did no post-adoption screening. The adoption was facilitated by a proxy acting on my parents’ behalf. Once I got to the U.S., nobody ever came to our house to make sure I was OK. Fortunately, I was.

My identity wasn’t important … until it was, when I entered my late 50s. I was an only child. Most of my older relatives were dead. I felt alone. I decided it was time to find my roots. As an adoptee, this a decision only you can make.

I began working with a Greek-speaking friend to find some answers, and my adoption papers from the orphanage in Greece had lots of them. All of a sudden I had a new identity: My name was Eftychia Noula, and I was the daughter of Harikleia Noula from Stranoma, a village in western Greece.

I’ll never forget the moment in June I got an email that said I should sit down before reading. My husband and I were on our way to dinner. I opened the email and immediately burst into tears. In a few sentences, I learned my mother was still alive — and she had never forgotten me.

Like me, my mother spent many years believing lies about our separation. She became pregnant at 19. When I was a month old, her grandfather instructed a family friend to bring us both to Athens. When we got there, the woman told my mom she was taking me to an institution where I’d be kept until she could find steady work. Instead, she took me to an orphanage. She never saw me again — until she was 80.

After receiving contact from my Greek-speaking helper, the village president walked into her home and said, “Harikleia, you’ve won the lottery.” When she said she didn’t buy a ticket, he said, “Nevertheless, you’ve won the biggest prize. Your daughter who was lost is looking for you.”

She fainted. When she came to, she told the village president — who is also our relative — that she wanted to see me.

Soon after receiving the email, I spoke to her on the phone through a translator. My biological mother had one question: When are you coming?

My husband and I had a trip to Greece planned for later that year, but a major part of me wanted to get on a plane right then and see her. My husband agreed, saying, “We’re not millionaires, so we can’t say money is no object. But money is no object because this is your mother.”

A week later, my daughter and I arrived in Athens. The entire family showed up at the airport to greet me. The crowd parted and there was a short little lady with this huge bouquet of flowers. My mom. She shoved it at me — then we both cried.

It took me 59 years to find her, and then another four hours to drive the winding roads to the village, during which my daughter and I were terrified: There were no guardrails, only thousand-foot drops off the mountain.

Once we got to the village, even more people gathered to see me. I was completely overwhelmed. They were hugging me and grabbing my cheek. I didn’t know who these people were. But they were my family. I hadn’t been forgotten. That was one of the greatest gifts I’d ever been given.

At the end of that week, I didn’t want to leave. Greece felt like home from the minute I got there. It’s a bond I can’t explain. Since then, I’ve gone back to Greece 44 times in just six years. The greatest compliment I ever got was when one of my cousins said, “Eftychia is one of us now. She understands the Greek mentality. She’s adopted the Greek habits. And she’s always here, so she’s one of us.”

The greatest compliment I ever got was when one of my cousins said, “Eftychia is one of us now."

When I bought a house nearby, my aunt said, “Now Eftychia has roots.” It still makes me cry when I think about it.

For a while, I had trouble forgiving my great-grandfather’s actions. I’m not sorry I was sent to the United States. I never would’ve had the life I had now here in Greece, in a small village. I probably wouldn’t have gotten an education, like my mom, and lived a life of hard farm work.

What I couldn’t get past was, how could he do this to someone in his family? I can’t ask him, or the woman whom he enlisted to bring me to an orphanage — both are long dead. I realize now it was a different time with different social norms — you can’t judge people based on our standards today, because they didn’t live beneath them. Part of me thinks he knew I’d come back. I was written into the family record, or merida. That name on that piece of paper is what allowed me to get my citizenship. A year after arriving in Greece, I put a flower on his grave.

Not all Greek-American adoptees get the closure I did. Since discovering my family, it’s become my mission to help others find this part of their life, and so I founded The Eftychia Project in 2019, a nonprofit that helps reunite Greek adoptees with their Greek biological families.

Through The Eftychia Project, we help other Cold War-era adoptees from Greece reconnect with their families. So far, we’ve facilitated the reconnections of 22 people with their birth families in the span of four years, and have been contacted by hundreds of families in Greece and the U.S. asking to find relatives. Next month, The Eftychia Project is hosting a conference for fellow adoptees in Greece. All this means I’m in Greece a lot — which is a wonderful thing.

Today, most people in my life call me Eftychia. That’s the name my biological mother gave me. It means “happiness.” She couldn’t have known it then, but my name was like a prophecy: I found happiness when I returned home to Greece.